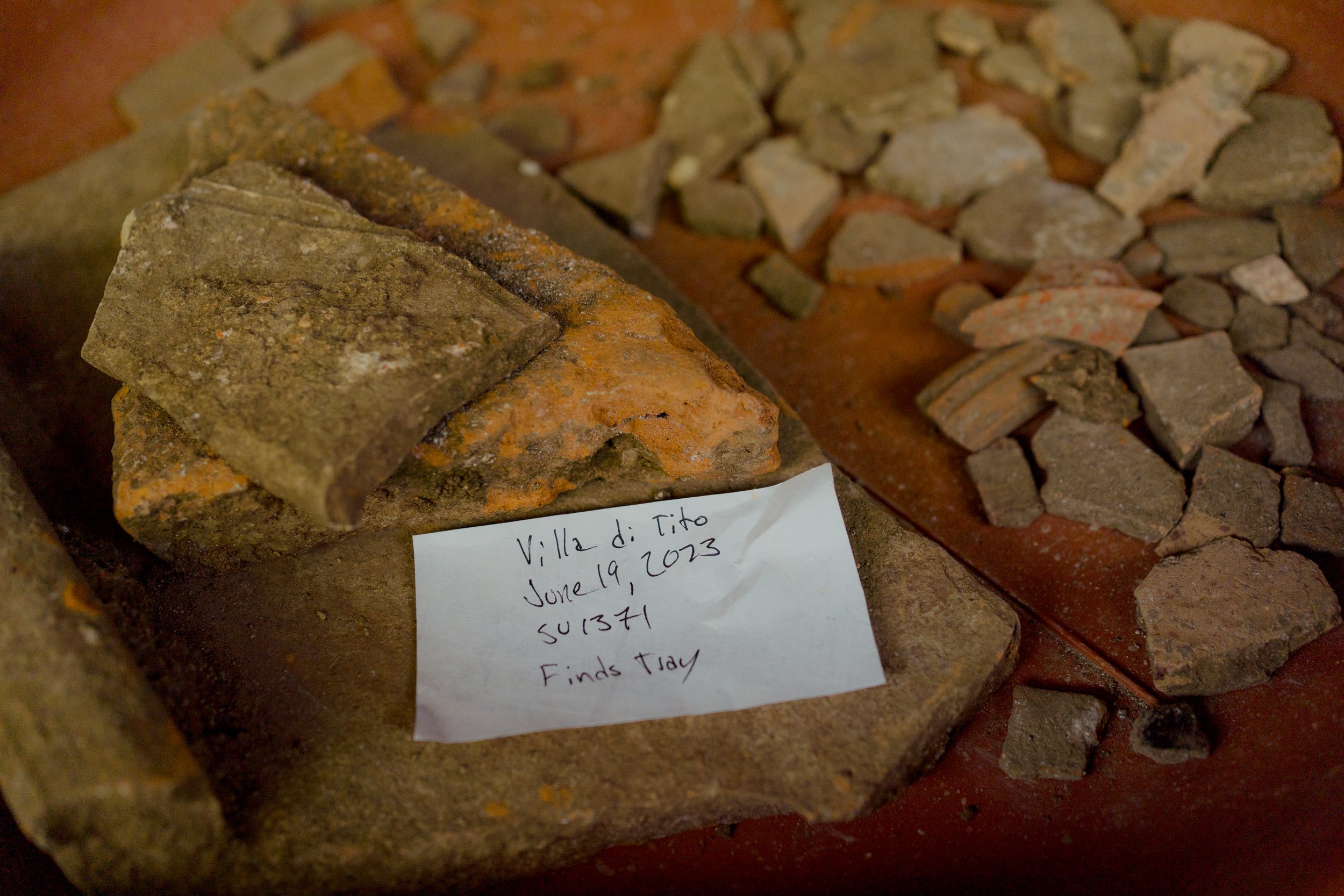

Students at Saint Mary’s University are helping to peel back layers of the past at a Roman villa dating back more than 2,000 years in central Italy. A vivid story from ancient history is emerging at the Villa of Titus excavation site in the Apennine mountains, about 70 kilometres northeast of Rome.

“Based on the artifacts recovered this year, it seems mostly likely that the building was residential,” says Dr. Myles McCallum, Associate Dean of Arts and co-director of the archaeological research project that is also home to a field school. “We found toiletry items such as bronze tweezers and spoons for applying makeup, bits of furniture one might find in a Roman house and lots of pottery used for cooking, all of which indicate a domestic use of the building.”

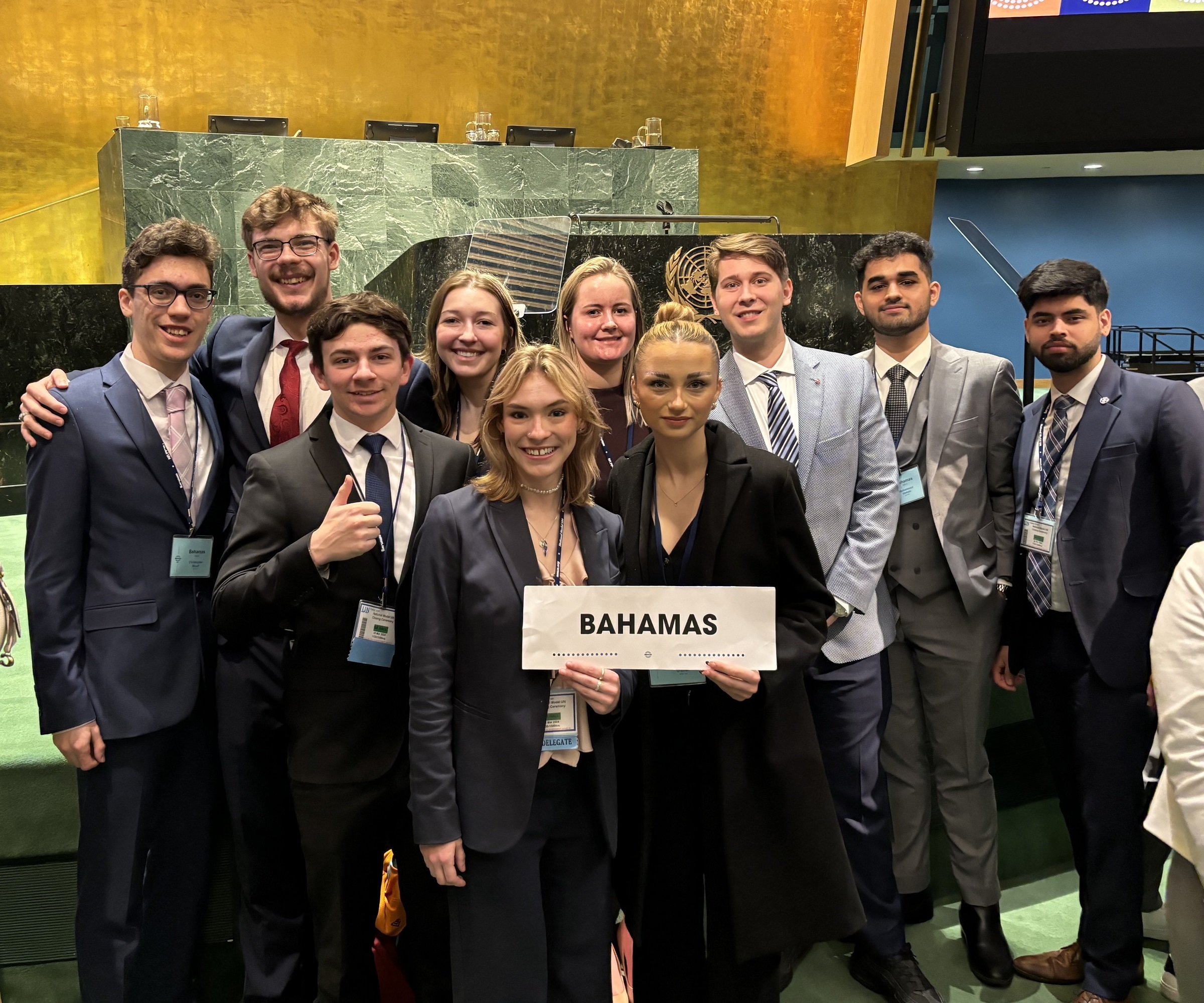

Eleven Saint Mary’s students and two alumni participated in the field school this May and June, along with six students and several researchers from McMaster University. Offered by the Ancient Studies program in our Department of Languages and Cultures, the study abroad opportunity launched in 2018 and also took place in 2019 and 2022. By working on an active research site, students learn the basics of environmental archaeology, excavation and artifacts analysis, and some even contribute to published research reports and articles.

“These skills all build on each other. You dig things up physically, clean things off and take pictures and drawings of them to try and understand and identify them. You measure them, you fill out paperwork, you log information into a database,” says McCallum.

“You put it all together and it adds to that understanding of what life was like 2,000 years ago in a different part of the world. It engages every part of your brain, the frontal lobe big-picture stuff. So that’s a big deal for students because no matter what you do in life, you’re going to have to be able to pose questions and figure out how to answer them.”

The research follows a theory that the monumental two-storey structure was built in the first century BCE for the emperor Titus, who reined 79-81 CE during the Second Dynasty of the Roman Empire. As more of the intact brick walls emerge from the hillside, “we understand much more about the building’s overall plan, as a villa with a central courtyard on a large terrace,” says McCallum.

Researchers found evidence this year that the complex was occupied for about 120 years. They also discovered signs of a previous building at the site, which had an adjacent well and large garden area.

“So people were there for a few hundred years in the smaller building, then built something much bigger on top of it. We also know that the villa went out of use in the second century CE, but we’re not entirely sure why,” McCallum says.

The main goal of the project is to reconstruct the daily lives of the enslaved workers, the subaltern people who grew crops, made bricks and wine, pressed olives for oil and engaged in cleaning, building, mining, woodworking and metalworking. Much of their economic activity may have taken place in the building’s basement (cryptoporticus), which had a large storage room, a door where carts could load and unload, and possibly also living quarters.

“Next year, we’re going to expand our exploration of this basement area,” says McCallum. The first step will require heavy equipment to remove hundreds of tonnes of stone and earth that had collapsed into the lower level, and then students will have a chance to excavate.

“It’s interesting because we think we know a lot about slaves during the Roman Empire, but nobody wrote about them, at least not from a social-historical perspective. So archaeological evidence is really the only direct evidence we have of what their lives were like. As a focus of research, it’s pretty recent,” says McCallum.

The villa sits high above the Velino Valley’s Lago di Paterno, a freshwater lake considered to be Italy’s geographical center and a once-sacred site connected to the goddess Vacuna. The University of London is conducting archaeobotanical research there with pollen coring, studying changes to the landscape and its flora and fauna over a 15,000-year period. “So that will be interesting, to tie in the human relationship with the landscape and environmental history too,” says McCallum.

Other notable finds have been oil lamps, bronze coins, glass perfume bottles, mosaic flooring and tiles, and transport amphorae (containers) that carried goods from as far as Spain and North Africa. Also intriguing is evidence of a ritual to seal off a well—including a silver mirror and a baby suckling pig, both sacrificed in hopes of a divine blessing for the house being built over the well.

The Villa of Titus project team also includes co-director Dr. Martin Beckmann of McMaster University and researchers from universities in Italy, the U.K. and the U.S. With support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Saint Mary’s is building on its existing strengths in archaeology research and education, deepening its cultural exchanges and academic connections with Italy’s museums, archaeologists and academic community.

“Experiential learning and study abroad opportunities are an important element of what we do in our program and in the Faculty of Arts,” says McCallum. “We’re working on developing more of these opportunities, and our students are embracing the chance to do this.”

Three other field schools took place in Italy this summer, including Sacred Space: Rome, from Ancient to Modern, offered by the Department for the Study of Religion, plus two in the Pisticci region, under a new dual stream Colonialism and Migration: Ancient and Modern field school:

the SJCS Migrant Justice Field School, offered by the Department of Social Justice & Community Studies; and

the Metaponto Archaeological Field School, led by Dr. Sveva Savelli and the Ancient Studies program for the second year in a row